Community-Driven

The Godot project is often touted as a shining example of community-driven development. However, upon closer examination, a web of contradictions emerges, casting doubt on this claim. While some contradictions may be expected in any endeavor, what truly raises eyebrows is the leadership’s failure to acknowledge or resolve these issues, leaving a trail of hypocrisy.

This issue can be encapsulated in this short satirical piece which exposes Godot’s so-called “ecosystem” as a collective business of its leadership:

Juan @reduzio Linietsky: "The idea is that Godot shouldn't just be an open-source project."

— Andrii Doroshenko 🇺🇦 (@Xrayez) March 24, 2024

God's away on business! 🤣 (Sound on!)#WaitingForBlueRobot #Godoverse #IndieGameDev #IndieDev #GameDev #FOSS #OpenSource #Scam #Grift #Ramatak #W4Games pic.twitter.com/JsNdYSfj7K

Contradictions are not inherently problematic as long as they are eventually identified, addressed and resolved. However, when the leadership of Godot fails to acknowledge or resolve these contradictions, it becomes a matter of their hypocritical behavior.

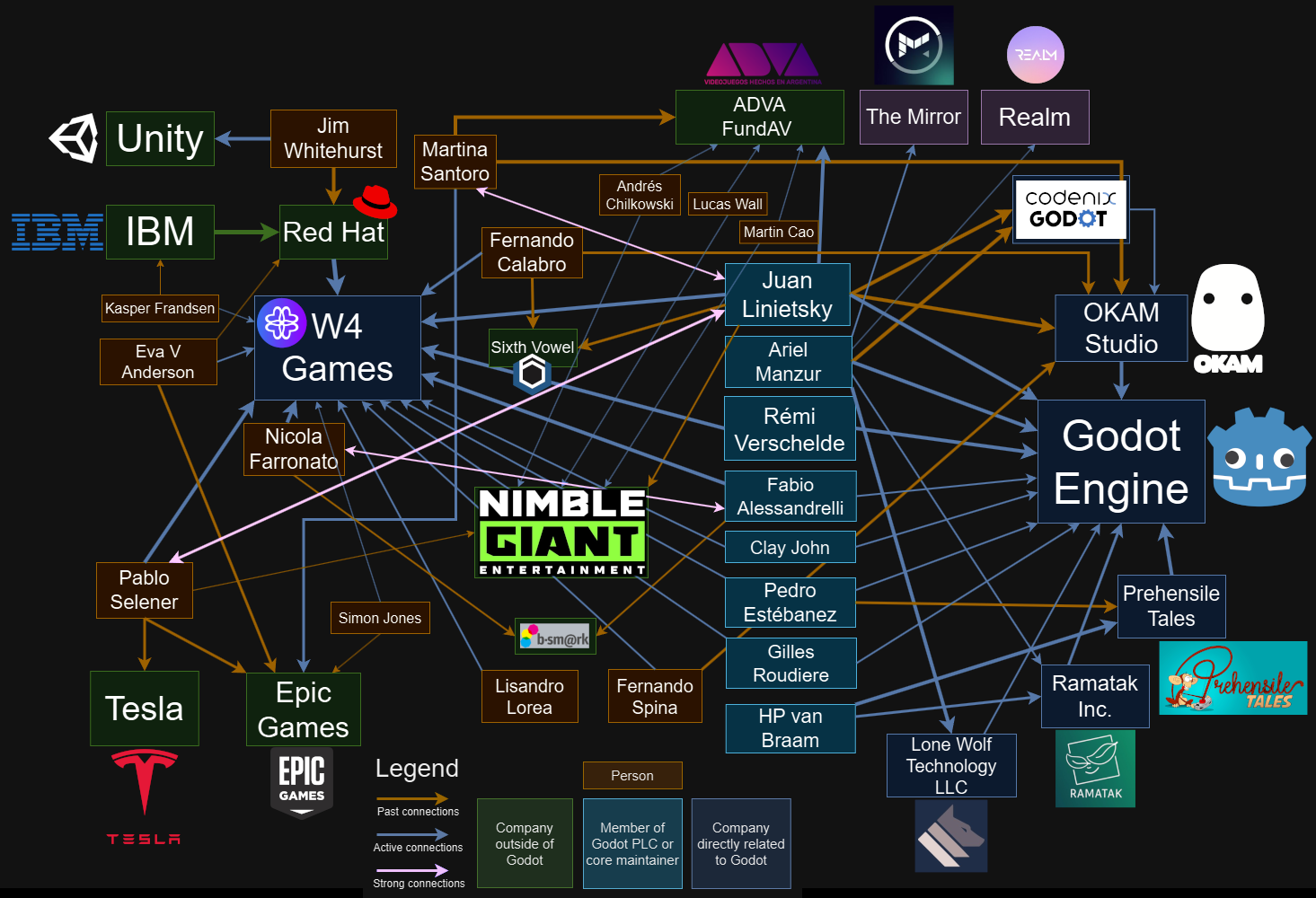

Godot Engine's public relations and connections.

By the time of writing this book, Godot’s development vision and philosophy remain undefined. In truly community-led open-source projects, a clear development vision and philosophy (or principles) form the bedrock of their success. It is very likely that Godot’s leaders deliberately neglect this aspect, see Waiting for Philosophy.

Another essential aspect of successful community-led projects is a strong sense of responsibility, especially concerning donations. However, in the case of Godot, there are concerns about the commitment of its leadership, including paid core contributors, to this crucial attribute.

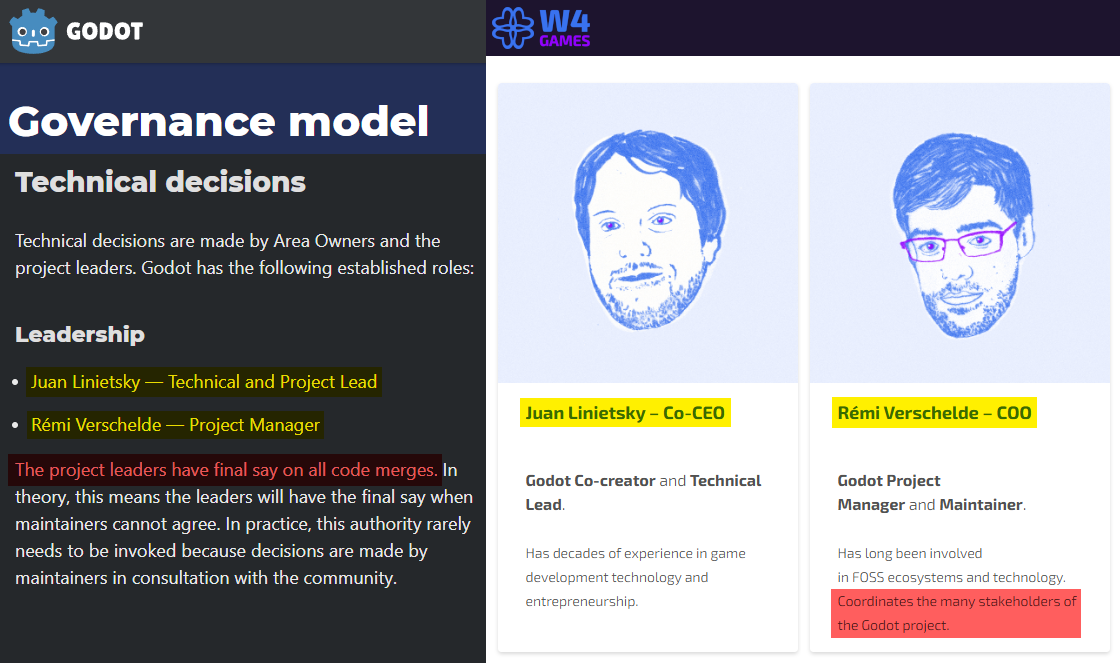

Community-led projects thrive on the principle of bottom-up development, where community leaders are trusted to guide the process. Yet, Godot takes a different approach by heavily relying on trust, but often in a selective or autocratic manner—a top-down style that contradicts the essence of community-led efforts.

Curiously, when this discrepancy is brought up for discussion within the Godot community, they suddenly adopt an opposing stance to the supposed bottom-up principle or horizontal structure, as promoted by the lead developer, and express a preference for a more hierarchical, top-down approach. To demonstrate this discrepancy, Juan Linietsky disingenuously asserts, emphasis mine1:

Godot has a very horizontal community and contributor model. We strive to discuss everything publicly and move forward based on agreement. Both the newcomers and the most experienced contributors will discuss and explain their ideas, make sure everyone else is in the same page, and try to reach agreement with others.

The “horizontal” part suggests that there’s a relatively equal distribution of responsibilities and decision-making among the community members and contributors, as opposed to a hierarchical or top-down approach. This implies that a lot of people have a say and have power over the decision making process.

In contrast, the official maintainer of Godot, Yuri Sizov, trusted by Godot’s leadership in everything he says and does to represent Godot to the public, claims the following, emphasis mine2:

Definition of Godot as “community-driven” doesn’t put community in charge. It puts community interests in front, but it doesn’t mean that there is democracy or design-by-committee process. In fact, I am strictly against it and in favor of opinionated decision making process with few decision makers.

In this case, the “opinionated decision making process” and “few decision makers” leads to hierarchical, top-down approach. This clearly goes in contradiction to Juan’s “horizontal” model often touted to the users of Godot.

Many members of the Godot community do not pay much attention to the claims and promises made by the lead developer. However, if you conduct your own research, you will find numerous contradictions within Godot that the leadership either ignores or refuses to address, which is the epitome of hypocrisy. Remember that words are not equivalent to actions; just because Juan claims he doesn’t decide anything doesn’t mean it is true.

So, the question arises: which community-led approach does Godot truly follow? The governance page seems to provide an answer3, but upon closer inspection, a curious twist emerges. The project conveniently redefines “community-driven” as “community-minded,” subtly substituting distinct concepts, akin to a “fine print” maneuver found in contracts.

Godot insists that feature development isn’t prioritized by any corporate entity. However, grants from different companies do influence Godot’s development in a specific direction, as well as financial donations from individuals, like Patreon contributions, where only Patrons hold voting power in the end, not the broader community, see challenged claims in the Democracy chapter.

Without further ado, let’s dive into the inner workings of the renowned open-source happenstance, Godot—a project supposedly driven by the community. Inspired by the enigmatic character from “Waiting for Godot,” the project’s name holds a deeper significance, urging us to look beyond surface claims and uncover the reality behind the scenes.

Companies vs FOSS

Someone may ask: “What’s wrong with that?” A valid question indeed! You may wonder, “What’s wrong with the Godot project’s leadership presenting themselves as community-driven while exhibiting signs of a commercial company?” Well, the issue lies in the apparent dissonance between these two aspects which must be resolved.

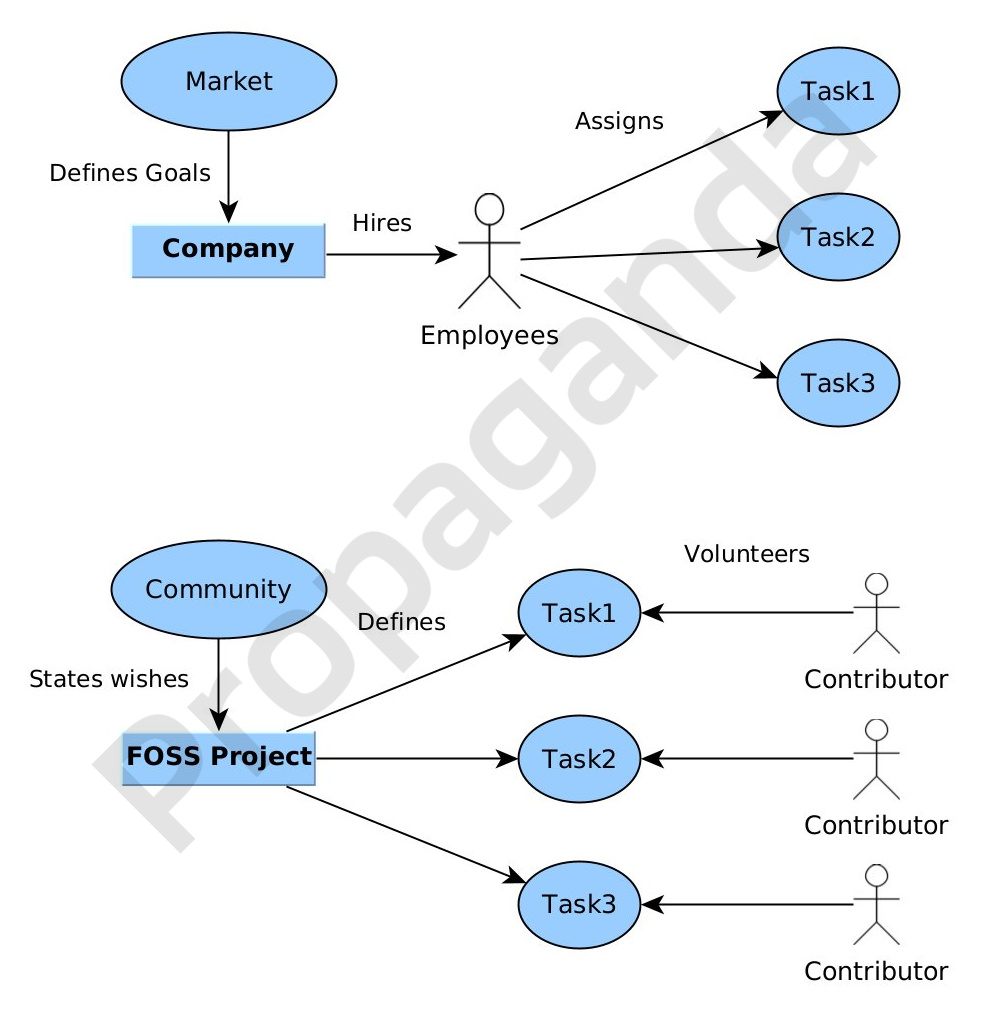

Lead developer of Godot once shown his understanding of open-source governance model in relation to commercial companies by drawing the following diagram4.

There are several issues with Juan’s diagram. First, I’d like to clarify that even if Juan portraits the bottom model representing governance of all FOSS projects, in reality that’s just Godot’s model, not FOSS in general.

-

Notice how Employees assign tasks. However, we don’t see any equivalent action described in Godot’s “FOSS” model. Contributors don’t necessarily choose tasks here. They might be asking for permission from Godot’s leadership to work on tasks, or something completely different.

-

Market doesn’t define goals. Market creates a chain of supply and demand. Goals are defined by the Company to meet a particular set of demand. This is what exactly so-called FOSS model represents when Community states wishes. Even then, ironically, Godot’s model doesn’t contain goals, which proves that Godot has no defined purpose. The problem is that Godot’s leadership has not defined those goals publicly in the first place, so they start to wrongly assume what community really wants, and speak for community.

-

Model shows one visual unit of Employees and several Contributors. This is how Juan introduces a visual bias into his model, as if companies have less people working on a project. For instance, here’s what Juan says, when comparing Godot to O3DE in terms of number of people working on a project5:

I don’t think that’s the case, there is near 2k people working on Godot and it’s one of the largest projects on GitHub (and growing). Not even Amazon with a hundred paid employees working on O3DE is close, mostly IMO due to the high engineer compatibility of projects so organic.

While an open-source project may have “thousands of contributors,” in reality most of them are one-time committers. What really matters in this context is the number of active developers incorporating changes to a project, and not the total number of them, so Juan’s statement is extremely manipulative. Additionally, the number of Godot contributors is closely correlated with overzealousness of its community, as you’ll discover in subsequent chapters.

Moreover, some people may harbor the mistaken belief that if development appears stagnant, the project is devoid of a future or something similar. In reality, when there are seemingly no changes, this may signal the project’s stability and robustness—qualities that are frequently paramount for users of software anticipating sustained, reliable functionality.

If we talk about decision-making process, it is still Godot’s leadership that determines what’s being worked on, not contributors. There’s absolutely no do-ocracy in Godot. The illusion portrayed as the freedom of choice comes from the fact that contributors choose from tasks already defined by Godot’s leadership. They cannot choose to work on anything not chosen by leadership, even if majority of community expresses a demand for something. Of course, contributors are free to start to work on something which wasn’t decided by Godot’s leadership beforehand, but doing so would be relying on luck for the most part.

Even if someone creates a pull request for a popularly requested feature, it may not be merged, and not necessarily because of quality, but due to other reasons, like the burden it imposes on maintenance. However, Godot’s leadership could delegate maintenance of a feature to someone who created it (the do-er), yet they don’t delegate such privileges for the most part. And maintenance equals to decision-making power. In truly community-driven projects, we’d see several people managing and merging pull requests, but even after a decade since Godot is open-sourced, we don’t witness this becoming a common practice within Godot.

If we address all the issues in Juan’s model scrutinized above, it will bear a striking resemblance to a typical company structure. The sole significant distinction lies in the fact that contributors who dedicate their efforts to a company named “Godot” do so voluntarily, without receiving monetary compensation. The number of active individuals considered as “employees” of Godot remains mostly limited to a few people. As frustration accumulates, attentive contributors may observe that the donations are used to increase the salaries of the leadership and a close circle of trusted members, rather than expanding the workforce by hiring experienced game engine developers, as you’ll find out in Recruiting. Consequently, the workload remains overwhelming and unresolved.

Syndicate

Look at what Juan Linietsky, the lead developer of volunteer-developed Godot, has been telling Godot community all this time6:

- There is no company behind it [emphasis added]. It’s owned by every single of its contributors.

- We don’t compete with Unity, Unreal, etc. In fact they are free to use any of our code.

- We make it because innovating is fun, and out of love for those making games.

For your information, Godot’s leadership co-founded several commercial companies around Godot in official capacity and in the same person, including but not limited to:

| Company | Co-Founders | Services | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| W4 Games | Juan Linietsky, Rémi Verschelde | Online Multiplayer, Console Porting | W4 is often referred to in the third person by Godot PLC, as if it were a fully independent company. |

| Lone Wolf Technology | Ariel Manzur | Console Porting | Promoted at Godot’s official documentation. |

| Prehensile Tales | Hein-Pieter van Braam | Various Services, Consulting | Godot Editor executables for Windows are code-signed by this company. |

| Ramatak Inc. | Ariel Manzur, Hein-Pieter van Braam | Development and Monetization of Mobile Games | Ramatak was mentioned by Emilio Coppola, nominally Executive Director of Godot Foundation, and Juan Linietsky at GDC 2023.7 |

All of them were co-founded by members of Godot PLC, forming a syndicate of companies. Collectively, they created a conflict of interest in relation to Software Freedom Conservancy and Godot Foundation.

Let that sink in for a moment. On Steam discussions, Rémi Verschelde, the project manager of Godot, previously asserted that there’s no business model behind Godot8, emphasis mine:

There’s no business model behind Godot, it’s free and open source forever, simply because that’s what we want to make. There is no company behind the project, only individuals with a common vision (and a US charity handling our legal and fiscal matters).

As others mentioned, we do have a crowdfunding campaign on Patreon (+ some direct donations via PayPal) which bring us enough funds to hire 2.5 of our contributors full time to speed up the project development (I’m one of those since a few months).

Eventually what we want is for thirdparties to develop business models around the engine which will benefit the community as a whole. There are already some Godot contributors who have their own company and do work for hire or paid support for studios.

In light of the above information, the statements “there is no business model behind Godot” and “there is no company behind the project” turned out to be big lies. They assured the community that this would never happen because, ironically, it’s “what they want to make.”

The so-called “third-party” companies around Godot are not third-party at all when the ultimate technical decision-makers, Juan and Rémi, remain at the helm of both the supposedly non-profit Godot and the for-profit companies mentioned above.

While there are certainly third-party companies around Godot, this does not eliminate the problem of the conflict of interest that Juan, Rémi, and other members of Godot PLC have regarding Godot and the companies they co-founded.

This situation exposes a contradiction in a non-profit initiative: there’s ambiguity surrounding the participation of project leaders in for-profit ventures, which directly contradicts the project’s ethos of transparency. Because of its non-profit nature, the project cannot openly endorse or promote those commercial entities. However, the undisclosed association of project leaders with for-profit companies created specifically for Godot presents a dilemma. Disclosing these ties would violate the non-profit mission, but hiding them perpetuates the lack of transparency. This loop can be broken in these ways:

-

Declare that Godot is a hybrid organization, where non-profit and for-profit entities are intertwined, while ensuring full disclosure of any apparent conflict of interest.

-

Significantly expand the number of people allowed to make the final decision on all code merges, beyond just two people. This would minimize the risk of the project being held hostage by stakeholders.

-

Members of the Godot PLC involved in for-profit ventures must leave the Godot Project and appoint new leadership to ensure community-driven development at all times.

However, even these solutions cannot repair the betrayal of trust Godot contributors would experience after these declarations and changes. Godot’s popularity depends on the idea that it is a pure open-source project. It would not be able to attract those “thousands of contributors” if Godot were declared a hybrid organization from the start.

Remember that in the past, Godot was a closed-source, in-house game engine for quite some time. Before they open-sourced the engine, the co-founders of Godot, namely Juan Linietsky and Ariel Manzur, co-founded Codenix9, a game development consulting company. Through Codenix, they licensed Godot to third-party companies in Argentina, which is now defunct.

At the time when Juan Linietsky found himself bombarded with criticism over his and other PLC members’ business ventures tied to Godot, he craftily employed a little spin. He cunningly referred to these companies as “satellite” communities, allegedly separate from the official Godot project, which posed him as a highly hypocritical individual, once again10:

It’s just amazing for me to see that Godot has grown so massively, even this past year, that not just the official communities grew huge, but there is now an infinity of smaller satellite communities unattached from the official one..

Juan made those statements in an effort to distract from the scandal. He urged people to donate to Godot as if it was on the brink of bankruptcy, even though they had received $8.5 million in funding from venture investors at W4 Games, emphasis mine11:

The project tapped into reserves to do more hires in order to complete Godot 4.0 (and now 4.1). This was successful and you can now enjoy it! But money is running out as the funding went cashflow negative..

Whereas W4 Games, a for-profit company co-founded and operated by Juan himself, literally pledged to support Godot’s project financially:

Additionally, W4 Games pledges to support Godot financially with no-strings-attached donations to the project.

Imagine being an investor in W4 Games. While nobody expects W4 Games to donate all their money to Godot, as an investor, you would expect W4 Games to stand behind their publicly declared pledge and support Godot if there were a dire need to secure the jobs of existing contributors who are hired by Godot to work on the engine either part-time or full-time. This is particularly crucial since the business of W4 Games depends entirely on the success and adoption of Godot. Hence, it would not make sense to portray the situation as if Godot is in dire financial straits and entirely dependent on donations from independent developers.

A respectable community member of Godot accurately outlined this situation:

To say W4 Games “is unrelated to the Godot project” is pretty disingenuous. That investment was made on the popularity of Godot, not you and Remi personally. And now to say “money is running out” and “development pace will probably go down” when you have $8.5M is a total scam.

It’s worth clarifying that one of the definitions of the word scam is a dishonest scheme. You can read this article as an example to understand in what other contexts something could be considered a scam, which ironically uses the “Waiting for Godot” analogy to convey the message. 😁

The video below highlights Godot’s commercial agenda, revealing that it is more expensive for indie game developers to use it on consoles compared to Unity:

Plenty of other people outside the Godot community share these insights:

I am sharing a lot about #Godot/#W4Games recently, following the reveal of the console port pricing, but it is just so ostentatious conflict of interest example and the leader being the main one here sharing hate/arrogance over other engines is...

— Pawel (@pawel_developer) December 13, 2023

🧵 Thread#TruthAboutGodot pic.twitter.com/U7xjacYwGK

I have been saying this for far too long now. Godot is a fantastic engine but W4 games has tainted its reputation. Here is Juan Linietsky claiming that W4 Games is unrelated to Godot when he was asking users for money for the Godot foundation after having raises $8.5M with W4. https://t.co/CpwrAjpjSC pic.twitter.com/vqawO1ZqwT

— Carson K. (@CarsonKompon) December 13, 2023

At present, the Godot Foundation does not offer free console support. It is a common misconception among Godot users that the Foundation is unable to provide such support due to being Open Source. But other open-source and source-available projects, such as LibSDL, Haxe, Monogame, Cocos or Defold, do offer console support free of charge. This is because other projects view console ports as a means of attracting more developers. For example, the following is a statement from a board member of Defold:

W4 is selling console access as a part of their business. In Defold we see console ports as a way to attract more developers. These developers will hopefully release successful games. Which will attract more users. Which will attract corporate partners. Which will generate money.

— Björn Ritzl (@bjornritzl) December 12, 2023

To further demonstrate that providing free console support is possible, here is what the Godot community provides, unofficially:

Prominent game developers have identified the same issue, and you can find a compelling blog post that thoroughly refutes Godot’s claims about not supporting free consoles:

In response to the @godotengine foundation announce about no port (pointing at W4 option) I wanted to say some things. Also I plan to share my porting work when I can.

— Claire Blackshaw (@EvilKimau) September 4, 2024

Video: https://t.co/snmuQ2tyQT

Article: https://t.co/a72WFczEjW

Some excerpts from the blog:

[…] The smart short term decision is to use Unity or Unreal which pound for pound are more capable engines able to ship higher quality games today. I’m investing in tech, my studio and frankly trying to build a house instead of renting one. So no, I don’t want W4 games as my landlord.

Notice how Unity and Unreal, despite delivering higher-quality products, are portrayed as only valuable in the short term. This is because Godot supporters are invested in the so-called “bright future” of Godot. One shouldn’t rely on wishy-washy hopes. Godot hasn’t arrived and never will! 😏

There is a big issue that the key maintainers and founders of the project are also the key figures at W4 and that is always going to be a hard needle to thread. […]

Again everything I’ve seen is people are mostly being above board and good but I don’t want to rent, I want to buy. So engaging in commercial agreements with W4 games is not in my studio’s best interest at this time.

It’s worth noting that comments like “There are no villains in this story. I think everyone is awesome” reveal a deep connection to Godot’s ideology. This doesn’t diminish the author’s expertise on the topic of consoles; instead, it underscores how even seasoned industry professionals can be swayed by their personal investment in a project, leading to blind devotion despite recognizing fundamental issues.

With this, I just want to illustrate that even those who are in “love” with Godot can’t ignore these issues forever, and the more invested they are, the more they can experience what might be described as Stockholm syndrome. In the context of scams, Stockholm syndrome can occur when victims become emotionally attached to their scammer or the fraudulent scheme, even while recognizing the harm being done. This psychological attachment can lead them to defend or justify the scammer’s actions, despite the obvious exploitation. We’ll delve into this sociopsychological dynamic in the following chapters, as this is one of the key reasons why many still remain silent about their bad experiences with Godot.

Regardless, Juan’s disingenuousness regarding W4 Games’ involvement with Godot is extremely difficult to deny here. W4 Games investments come from investors that are familiar with FOSS or were in the past prominent figures. Godot’s leadership carefully cherry-picked venture investors who have expertise in Open Source, those who Juan can fully trust for his scheme (see Trustocracy) and/or knows how to allure them, since Open Source investors are more susceptible to manipulation due to its ideological nature. Once the foundation is ready, they might start to participate in a larger scheme to lure in unsuspecting investors outside of Open Source arena.

Joseph Jacks, a prominent investor of W4 Games, once shared a series of enigmatic statements that seem to encapsulate his vision on embracing Open Source technology. Mind you, these statements hold a touch of irony, inviting us to delve deeper into his underlying motivation for investing in companies like W4 Games, emphasis mine12:

There’s no money in open source.

There’s only niche money in open source.

There’s definitely money in open source.

Most of the money is in open source.

The only money is in open source.

There is no money, there’s only open source.

When you interpret those statements as stages, the last statement suggests this kind of future. 🙃

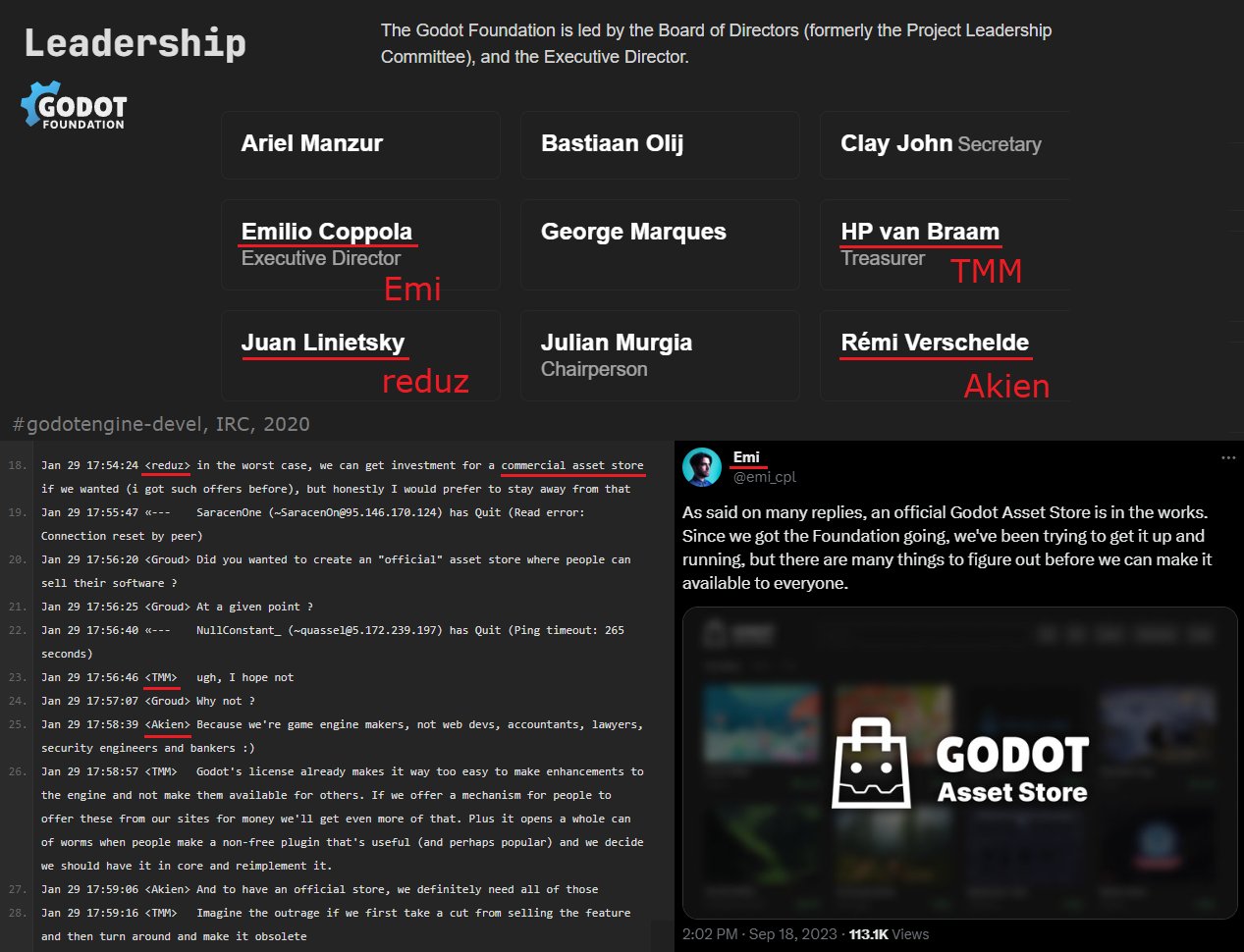

Godot has also made several inconsistent statements about the creation of the commercial Asset Store, which contradicts Godot’s non-profit mission. Initially, they claimed they couldn’t afford it because of Godot’s open-source nature. However, over time, they changed their stance, likely to cater to the growing number of Unity users who want an equivalent Asset Store in Godot. Here’s a public conversation between members of Godot PLC, retrieved from IRC logs13:

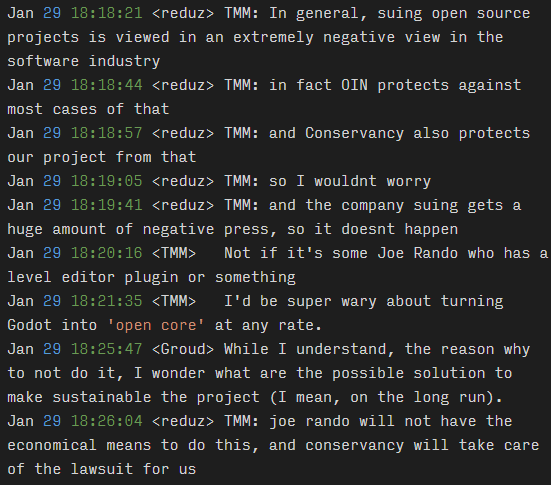

Juan Linietsky and others also discussed the possibility of facing a lawsuit in the context of Software Freedom Conservancy and creating a commercial Asset Store:

Contrary to what HP van Braam (TMM) said in 2020, Godot is becoming more akin to Open Core in its structure nowadays, given Godot’s for-profit companies such as W4 Games and Ramatak. This is especially evident when Juan presents Godot to investors as a so-called Open Ecosystem.

According to Software Freedom Conservancy’s Conflict of Interest Policy, the PLC Person, in our case these are Juan and other members of Godot PLC, must disclose their conlict of interest14:

Disclosure of Conflict When Present. Prior to any PLC or PLC sub-committee action on a matter or transaction involving a conflict of interest, a PLC Person having a conflict of interest and who is in attendance at the meeting shall disclose all facts material to the conflict. Such disclosure shall be reflected in the minutes of the meeting.

A PLC Person (or their family member) is engaged in a substantial capacity or has a material financial interest in a for-profit enterprise that competes with their Project.

None of the existing members of Godot PLC have disclosed any such connections. They eventually left the Software Freedom Conservancy15 in favor of the Godot Foundation. The individuals who make up the Godot Foundation also represent commercial companies. The problem is the lack of a controlling body. For more than a year, Godot has not submitted annual reports or financial statements, even though they are required to do so from day one as a non-profit organization:

Waiting for Godot Foundation financial reports? 🙃 pic.twitter.com/yVaJ14EUrk

— Andrii Doroshenko 🇺🇦 (@Xrayez) February 14, 2023

Since Godot is declared as a non-profit, it would be illegal for Godot’s leadership to control the funding decisions of both their for-profit companies and Godot as a non-profit project. Commercial shenanigans that exploit the allocation of grants among those companies, such as Prehensile Tales, instead of being handled by SFC directly, raise numerous questions16. While such maneuvers might be deemed acceptable for a commercial enterprise, the actions of Godot strongly suggest an exploitation of their non-profit status to gain unwarranted economic advantages.

Software Freedom Conservancy ignored all requests on this topic by the author of this book. Taking into account other ignored reports to SFC as you’ll read further, this means that both Godot and SFC are likely interested in this kind of scheme, despite apparent conflict of interest, especially when they use the same “graduation” rhetoric17. They both label it as a “graduation.” What this newspeak really means is that Godot betrayed the trust of existing Godot followers at that time. See what lead developer of Godot said years ago about Godot, before they left SFC18:

Given many FOSS projects recently went either proprietary or hybrid [emphasis mine] (and we which we will soon forget in favor of their forks), I want to remind all that Godot is owned by a not-for-profit, so this can’t ever happen.

Every bit of Godot is owned by the person that contributed it.

(Just to clarify, Conservancy, the not-for profit, owns the trademarks and is the fiscal sponsor, contributors own the code they contributed under MIT license)

Examining these facts, it becomes increasingly challenging to arrive at any interpretation that would deny Godot’s status as a hybrid organization now. The emergence of multiple commercial enterprises operating under the umbrella of Godot, overseen by the very leadership of the project, and the subsequent departure of Godot from SFC, serve as unmistakable evidence that Juan’s earlier assurances are, at best, fallacious.

As of the time of writing this book, no legal measures have been taken against the leadership of Godot. Furthermore, the author of this book no longer perceives ownership over Godot, as the right to contribute to its development has been revoked—a circumstance shared by a subset of other contributors, as you will discover in the concluding chapters of this work.

For some people, perhaps all of the above wouldn’t be so much of a problem and could be tolerated or mitigated, but Godot’s governance is certainly not the only issue at play here. Inefficient project management and the lack of Godot’s Development Philosophy are factors that contributed to Godot’s overall strategic issues as a project. It makes no sense to start engaging in commercial endeavors and trying to pitch business idea to investors before stabilizing the very product that you depend on. To quote an ex-moderator of Godot’s Discord server19:

Juan’s “Godot philosophy” was killing Godot… and definitely killing my bright eyed and bushy tailed vision of where Godot could go. So, I got again more vocal about Juan’s constant “It’s my engine, I’ll do it my way” take while claiming it is “community driven”.

28/ Juan's "Godot philosophy" was killing Godot... and definitely killing my bright eyed and bushy tailed vision of where Godot could go. So, I got again more vocal about Juan's constant "It's my engine, I'll do it my way" take while claiming it is "community dirven".

— LillyByte (@LillyByteGames) March 28, 2022

The saddest part of all this is that Godot fans either don’t care about these issues or even say that the developers don’t have to listen to their community:

Mark the words:

— Paweł 🔜 GIC, Poznań, 20-24 October (@pawel_developer) December 15, 2023

A community-driven project which Godot claims to be "don't have to listen to their community, if they don't want to."

They don't have to, yes, I totally agree, no way to force it, except only leaving it.#Godot #TruthAboutGodot https://t.co/2qAHieKzLe

The leadership of Godot has ingrained the idea that these dishonest practices are acceptable, while also falsely believing that Godot has quality features that, in their warped sense of ethics, justify those practices:

ya know what why are you getting so ryled up about this. even if they are being frauds they are delivering on their feature promisis including cons, important venues, and demos. none of these are cheep.

— KaziiTheAvali (@KaziiTheAvali) September 10, 2024

Satellites

The previous section referred to W4 Games, Lone Wolf Technology, Prehensile Tales, Ramatak as a syndicate, because of direct involvement of Godot PLC. This section, in contrast, lists some notable Godot satellites, where some Godot PLC members and notable Godot contributors/maintainers are working as employees as of the time of writing.

The Mirror

The potential partnership between The Mirror, the potential Roblox-like game development platform, and W4 Games, an Irish start-up aiming to “revolutionize” the online gaming market founded by Juan and others, further highlights the interconnectedness within the industry. W4 Games, with its cloud platform based on open-source technology, intends to “democratize” the online multiplayer market for independent developers, as they proclaim at their LinkedIn page. Should The Mirror flourish, it could become a primary source of income for W4 Games.

The convergence of Godot contributors working on both The Mirror and W4 Games, along with the personal connection between the managing director of W4 Games, Pablo Selener (a former employee at Epic Games), and Juan Linietsky20, raises numerous questions about the true nature of their collaboration.

Nevertheless, it is crucial to approach this information with a balanced perspective. The individuals involved with The Mirror21, such as Ariel Manzur, co-founder of Godot, and HP van Braam, a Godot maintainer, carry substantial weight within the Godot community. HP controls the toolchain required to build Godot for all supported platforms (including Apple platforms), and Godot binaries for Windows are code-signed via his commercial consultancy company called Prehensile Tales B.V.

While other contributors like Gordon MacPherson (from IMVU) and Aaron Franke have made significant contributions to Godot Engine, such as FBX/GLTF file format support for 3D models, their involvement in The Mirror adds an intriguing dimension to the situation. For example, Aaron Franke, who is now recognized as an official member of Godot, previously criticized Godot for its “community-driven” label because it’s confusing to other contributors22:

The README should reflect Godot’s policy, not go against it. Doing otherwise is confusing for contributors. Stating Godot is community-driven is misleading at best, so it shouldn’t be in the README. Most people will read “community” as “the whole community of users and developers”, not “the community of core developers”.

Even when Aaron explicitly stated beforehand that “This was not done in bad faith,” the leadership of Godot did not listen and refused to remove the “community-driven” label. HP van Braam rejected the pull request (PR), closed it, and locked the discussion, contradicting the principle of open discussion declared by the Godot project, and labeled Aaron’s pull request as a grievance:

Discussions like this don’t happen on a PR and never have. Opening a PR like is clearly in bad faith. I’m sorry you feel frustrated about the process but this is not the way to air your grievances.

If Godot’s leadership dismisses the input of contributors in such a manner, what can we expect in terms of their response to user input? Under normal circumstances, the developments at for-profit projects such as The Mirror could signify positive opportunities and collaborations. However, realistically, they present red flags that cannot be ignored23. The needs of such companies might dictate the future course of Godot (see Simplicity), potentially overshadowing the needs of the larger community that utilizes Godot.

The Mirror and Godot Engine partnership teaser

Whatever the case may be, Godot’s leadership is definitely interested in attracting even more followers to use Godot, even if it means gradually transitioning from platforms that are “easier to use” like Roblox to considering the use of Godot. This is particularly relevant since The Mirror is built upon Godot Engine itself. The leadership’s interest in expanding the user base is evident.

Since The Mirror is potentially the next Roblox, you should also be aware of potential exploitation of young game developers. In an investigation done by People Make Games titled “Investigation: How Roblox Is Exploiting Young Game Developers”24, they ask whether the kids making the vast majority of its content are being taken advantage of. An interesting fact: before a series of investigations by PMG, Roblox Corporation has been valued up to $45 billion, and now being valued at more than $27 billion by the time of writing this book:

Juan Linietsky might announce that he plans to resign from his position in Godot Engine, either by focusing on a closed-source or source-available fork or continuing his involvement through W4 Games and other companies, which would act as a financial resource and service provider to projects such as The Mirror. It is not unusual for a project like Godot to have commercial forks, especially due to its lack of out-of-the-box Customization. In fact, the first commercial distribution by Godot’s leadership already exist, and it’s called Ramatak Mobile Studio. Such commercial forks could entice contributors with investment opportunities, leading to a split within the community and possibly resulting in Godot stagnating as an open-source project specifically.

Conclusion

Given the absence of a clear development vision and philosophy from Godot itself, in essence, the project’s direction largely hinges on financial support from various sponsors, regardless of their nature, even extending to the gambling industry. It becomes evident that companies wield significant influence over Godot’s development direction, despite claims of community-led decision-making. Ethical considerations aside, the pivotal role of corporations cannot be ignored. The emphasis is on the decisive role that companies play in determining Godot’s development direction, regardless of the nature of those companies.

The discrepancy arises from the surface-level impression of Godot being purportedly community-driven, while exhibiting signs of a typical company structure. Historically, they have always operated as a “garage” game development and consulting company. They leveraged and benefited from Open Source due to the economic circumstances of Godot’s founders in the past. However, they lack the expertise to effectively manage community-led open-source projects. Godot gained traction primarily because of Rémi, an overzealous Open Source advocate who took the initiative and invested a significant amount of effort into promoting Godot. Additionally, potential grants offered by Latin American governments to promote Open Source technologies worldwide, including Godot, also played a role in its growth.

Godot’s leadership brainwashed their initial contributors, who were volunteers, that they would wield significant decision-making power in the early stages of Godot’s development. Without that initial injection of free labor, Godot wouldn’t have gained the level of traction it has now. Back when Godot was inconspicuous and insignificant, one tactic to lure in contributors was to pledge a project crafted by the community, for the community—an alternative to the “two big engines,” as Juan often points out. Juan promised them that they would be among the pioneers in this supposed gold rush, leading the charge in the so-called “inflection point” of challenging the industry giants and promising a supposedly bright future. Their misstep was in overselling to the public, making a bunch of conflicting or questionable statements and moves.

Over time, Godot’s leadership insidiously introduced corporate elements into the Godot’s so-called worldwide organization while simultaneously assuring their users and contributors that it would never be influenced by commercial entities. They consistently deceive people by claiming their organization has a horizontal structure to lure in even more followers and potential contributors. The actions of Godot’s leadership compared to their public statements, therefore, suggest that Godot is operating as an extremely sophisticated grift.

If Godot were to address all its issues and become a polished product, it would lose its raison d’être, as per the underlying meaning behind the name Godot. The essence of Godot lies in its perpetual state of being unfinished. If all its problems were fixed, Juan and his loyalists, presently engaged with W4 Games, would lose the ongoing opportunity to generate income. While this notion may seem bizarre initially, their perspective is rooted in the observation that if people are willing to donate to Godot for an incomplete or even a broken game engine, they internally reason: “It’s working, so why not continue as is while they contribute to Godot?”

In light of this, if Godot’s current dishonest practices were to go unnoticed, there’s a potential reinforcement of the notion that engaging in unethical and corrupt behaviors is permissible. Essentially, this blurring of ethical boundaries threatens to erode established principles of what is considered morally good, especially to those sharing democracy values. Therefore, it’s crucial for the wider game development community and experts in related industries to exercise caution regarding the lasting impact of Godot’s undue influence.

References

Juan Linietsky about horizontal community and contributor model - Godot subreddit.

Yuri Sizov about governance model of Godot - Godot, GitHub.

Governance model - Godot Engine website.

Companies vs FOSS model - By Juan Linietsky, Twitter.

Juan Linietsky on the number of contributors - By Juan Linietsky, Twitter.

Facts about Godot Engine - By Juan Linietsky, Twitter.

There’s no business model behind Godot - By Rémi Verschelde, Steam.

Codenix website - By Juan Linietsky, Ariel Manzur.

There’s no money, there’s only open source - Joseph Jacks, Twitter.

Godot Asset Store discussion - #godotengine-devel, IRC.

Godot’s Graduation: Godot moves to a new Foundation - By Juan Linietsky.

Changes to Godot Patreon - Godot Engine, Patreon.

Announcing Godot’s Graduation from SFC! - Software Freedom Conservancy.

Juan Linietsky on Godot’s future as organization - By Juan Linietsky, Twitter.

Juan’s “Godot philosophy” was killing Godot - LillyByteGames, Twitter.

Video Games Around the World - Mark J. P. Wolf (ed.), 3 June 2015.

The Mirror - About Us - The Mirror website.

Remove mention of community-driven and mention feature PRs may not be accepted - Godot, GitHub.

The Mirror – Godot Powered Commercial Game Engine - By GameFromScratch.com, YouTube.

Investigation: How Roblox Is Exploiting Young Game Developers - YouTube, People Make Games.